Romans 16:7 Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Israelites who were in prison with me; they are prominent among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.

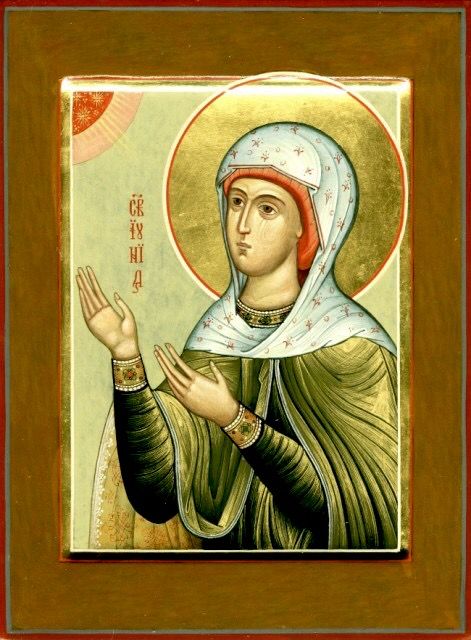

In my last post, “The Forgotten Female Apostle,” I drew attention to a neglected woman in the Bible: Junia, who Paul calls Prominent among the Apostles. Paul’s affirmation of Junia’s ministry testifies to his broader affirmation towards women’s leadership in the church.

In the recent past, many Christians have been hesitant to accept Junia’s position as an apostle, disputing it for various reasons. Therefore, we will deal with each objection in detail. Close examination of the evidence demonstrates that Junia was indeed a female apostle.

Junia or Junias?

When the New Testament was written in the 1st century, it was written without accent marks. Unfortunately, these accent marks determine whether Ιουνιαν is grammatically feminine or masculine. The name Ιουνιαν could refer to a woman, Junia, or a man, Junias.

In the 19th & 20th centuries, many Christian scholars argued that the apostle Ιουνιαν was a man, Junias. While the Greek is ambiguous, they often argued this not on the basis of its evidence in ancient literature but on the assumption that an apostle could not be a woman. Therefore, Junia must become Junias.

In a revealing statement, an influential 19th century commentary argues, “If, as is probable, Andronicus and Junias are included among the apostles…, then it is more probable that the name is masculine.” – Sanday and Headlam, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Romans. 1902, pg. 423.

We are forced to conclude, with Eldon Jay Epp, that “the description as a prominent apostle and the identification as a woman, for some at least, cannot coexist.” – Eldon Jay Epp, Junia: The First Woman Apostle, 2006, pg. 70.

The relevant evidence, however, paints a different picture. Origen, Chrysostom, Ambrosiaster, Jerome, Theodoret, and other early church fathers universally regarded Ιουνιαν as female. When Greek manuscripts began to be accented in the 9th century, they marked Ιουνιαν as feminine. The first person to suggest that Ιουνιαν may be masculine was Giles of Rome in the 14th century.

“Without exception, the Church Fathers in late antiquity identified Andronicus’ partner in Rom 16:7 as a woman, as did minuscule 33 in the 9th century which records Ἰουνίαν with an acute accent. Only later medieval copyists of Rom 16:7 could not imagine a woman being an apostle and wrote the masculine name ‘Junias.’ This latter name did not exist in antiquity.” – Peter Lampe, Junia. AYBD, 1992, p. 1127.

While Ιουνιαν could hypothetically be rendered Junias, that doesn’t mean Junias was necessarily a name in antiquity. To determine Ιουνιαν’s gender, we must ask: were Junia and Junias names that actually existed in the first century?

Junia was a common Latin female name. Over 250 instances of this name have been found in Rome alone, the location of the church that Paul wrote to and Ιουνιαν lived. The theoretical name Junias, however, is unattested throughout all of ancient literature. Scholars have examined ancient inscriptions, records and literature; attempts to find the name Junias have come up empty. The evidence leads us to firmly conclude that the name Junias did not exist.

As Bernadette Brooten summarized, “We do not have a single shred of evidence that the name Junias ever existed.” – Bernadette Brooten, Junia, 1977, pg. 142.

Some have attempted to salvage the view, despite its lack of evidence, arguing that Junias could be a contracted version of the name Junianus. However, this contraction is likewise unattested in ancient literature. Finally, such contractions do not occur with Latin names, which renders it impossible that Junias is a contracted form of Junianus (Cervin 1994).

“The only evidence adduced to support Junia as a contracted name comes by analogy with similar names ending in -ᾶς. No one has offered any evidence for the actual existence of this masculine name.” – Eldon Jay Epp, Junia, 2006, pg. 25.

While once regarded as a credible view, the lack of evidence for Junias’ existence, along with the evidence for Junia, has led to a scholarly consensus on this issue. Scholars are now in agreement that Ιουνιαν is a woman, Junia.

Apostleship Examined

It wasn’t until the RSV in 1837 that the name Junia disappeared from English translations of the Bible. For the reasons mentioned above, and thanks to the detailed study of many scholars, Junia reappeared in English translations in the mid-1980s.

Two scholars responded by arguing for a reinterpretation of the phrase “Prominent among the apostles”. Michael Burer and Daniel Wallace argued in 2001 that the phrase should instead be translated “Well known to the apostles”, thereby excluding Junia from the apostolate.

As Eldon Epp cleverly observes, “Over time, the male ‘Junias’ and the female ‘Junia’ each has his or her alternating ‘dance partners’—first one, then the other: first and for centuries, Junia with ‘prominent apostle’; then Junias with ‘prominent apostle.’ Then for a time Junia disappears from the scene, hoping upon her return to team up once again with ‘prominent apostle,’ only to encounter ‘known to the apostles’ cutting in during this latest ‘dance.’” – Eldon Jay Epp, Junia, 2006, pg. 72.

Both options are grammatically possible. The “exclusive” reading sees Paul as commending Andronicus and Junia’s reputation in the eyes of the apostles, but not being apostles themselves. However, this seems a surprising rhetorical strategy as Paul elsewhere dismisses appealing to the opinion of those supposed to be “acknowledged leaders” (Gal 2:6 cf. 1:8, 17).

“Paul repeatedly emphasizes that his calling and mission had and needed no human legitimation (Gal 1:16-17, 2:6). In the same way, he categorically rejects human valuation in 2 Corinthians (10:12), which he considers [according to the flesh] (10:2-4). Given this attitude toward others’ estimation, it seems highly unlikely that, in Rom 16:7, Paul would mean Andronicus and Junia are “esteemed by the apostles.” Such reliance on human approval contradicts every indicator of Paul’s stance on human judgment.” – Yii-Jan Lin. “Junia: An Apostle before Paul.” JBL 139, no. 1. 2020, pg. 202.

Around 2003, detailed responses to Burer and Wallace came from Eldon Jay Epp, Linda Belleville, and Richard Bauckham, demonstrating that the alleged evidence given for their case was overstated and erroneous. The most natural way of taking Paul’s statement is that Andronicus and Junia are prominent apostles.

This is confirmed by the historical data. The church fathers universally took Paul to be indicating Junia’s apostolic status. Origen and Chrysostom took Junia to be an apostle, acknowledging no other possibility, despite the counter-cultural nature of Paul’s statements.

“Indeed to be apostles at all is a great thing. But to be even amongst these of note, just consider what a great encomium this is! But they were of note owing to their works, to their achievements. Oh! how great is the wisdom of this woman, that she should be even counted worthy of the appellation of apostle!” – John Chrysostom. Homilies on Romans, 4th century.

The patristic data cannot be undervalued in this discussion. The fathers had no motivation for propping up a female apostle. On the contrary, they wrote at a time in which women were not appointed to church leadership. They interpreted Paul’s phrasing this way because they knew of no alternative.

“Writers such as Origen and John Chrysostom were educated native speakers of Greek. They had no reason for thinking Andronicus and Junia to be apostles other than supposing this to be the meaning of Paul’s Greek. If Burer and Wallace’s conclusion is right, then it is inexplicable that these Greek patristic interpreters should have read the Greek of Romans in the way they did.” – Richard Bauckham. Gospel Women. 2002, p. 179.

Circumstantial Evidence

The debate has often focused on the specific phrase that Paul uses to describe Andronicus and Junia. Often overlooked, Paul’s other statements about the pair provide some circumstantial evidence in favor of identifying them as apostles. He tells us that Andronicus and Junia:

- Are his relatives.

- Were in prison with him.

- Were in Christ Before him.

That they are Paul’s relatives indicates that they are Jewish. Their subjection to imprisonment with Paul must indicate that they were persecuted alongside him for preaching the gospel publicly.

“Indeed, it is hardly likely that a woman would be incarcerated in Paul’s world without having made some significant public remark or action. Junia said or did something that led to a judicial action.” – Ben Witherington III. Romans. 2004, p. 390.

Significantly, Paul claims that they were “In Christ before I was”. This sets Andronicus and Junia’s conversion within the early days of the church, before the gospel made its way out of Judea. They were not only Jewish, but likely members of the formative Jerusalem church.

“It is a detail that places them at the beginning of the new movement, increasing the likelihood that they were among those apostles who counted themselves as witnesses to the resurrection.” – Mark Goodacre, Junia: An Apostle before Paul. 2011, pg. 6.

The exclusive reading is unlikely based on Paul’s attitude towards his own inclusion in the apostles. If Paul were commending the two as “well known to the apostles” then he would be appealing to an external group, the apostles, without including himself in this group. This seems inconceivable when compared with the lengths that Paul goes to defend and proclaim his apostleship elsewhere (1 Cor 9:1-2, Gal 1:1).

“Could the apostle, who has to fight for the right to call himself an apostle, really use the term about another group? Could he afford to imply that he was not a part of a group commonly acknowledged to be “apostles”? If Paul’s intention was to suggest that Andronicus and Junia were well known to the apostles, we would expect him to have stressed his participation in that group.” – Mark Goodacre, Junia. 2011, pg. 8.

Conclusion

For such a short verse in a list of greetings, Romans 16:7 has generated a fierce debate. However, when the relevant evidence is examined, we discover that Junia is definitively a female name, and that she is most likely an apostle. This makes the best sense of the historical witness of the church fathers, the Greek phrase used to describe them, and the other information we are given about them.

While we might be troubled at the notice of a female apostle in the New Testament, and motivated to discredit it, the apostle Paul was not troubled. If we want today’s church to reflect what we learn in the New Testament, we can start by acknowledging the first female apostle, and commending her as Paul did.

Recommended Reading

Eldon Jay Epp, Junia: The First Woman Apostle. Fortress Press, 2005.

Richard Bauckham, Gospel Women: Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002, pp. 165–202.

Mark Goodacre, “Junia: An Apostle in Christ before Paul: A Neglected Feature in the Discussion of Rom. 16.7,” SBL Annual Meeting (Pauline Epistles Section), San Francisco, November 2011.

Yii-Jan Lin. “Junia: An Apostle before Paul.” Journal of Biblical Literature 139, no. 1. 2020, 191–209.

Bernadette Brooten, “Junia … Outstanding Among the Apostles” in Women Priests, 1977, pg. 141-144.

Richard Cervin. “A Note Regarding the Name ‘Junia(s)’ in Romans 16.7“. New Testament Studies 40, no. 3. 1994, pg. 464-470.

Ben Witherington III, Paul’s Letter to the Romans: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004, p. 387-393.

Linda Belleville, “A Re-examination of Romans 16.7 in Light of Primary Source Materials.” New Testament Studies 51, no. 2. 2005, 231-249;

Joseph Fitzmyer, Romans. Anchor Bible Commentary. Doubleday, 1993, pg 737-739

Thoughtful and challenging comments or questions are invited and appreciated!

Leave a reply to The Forgotten Female Apostle – The New Jerusalem Cancel reply